Louis Daguerre: The Man Who Perfected the Camera Obscura

2 5As a man of many accomplishments, Louis Daguerre's name is majorly associated with the history of photography—a history he himself started. Lomography presents a quick study of how Daguerre came to be the luminary that he is now.

Past Life: Daguerre Before the Camera Obscura

Before photography, the French Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was first known as the inventor of the Diorama and as a man of the visual and theatrical arts.

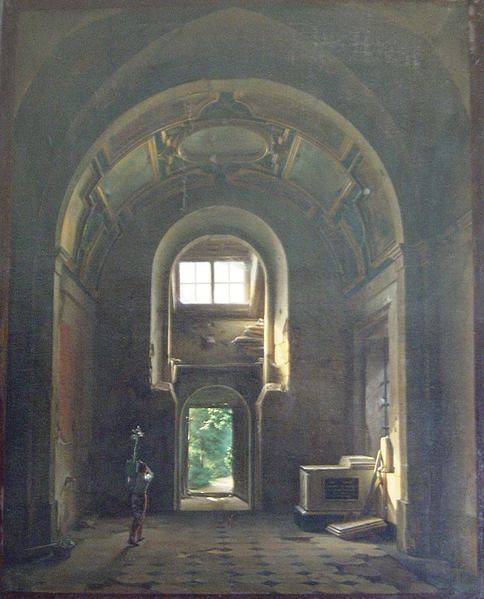

Under the tutelage of French painter Pierre Prévost, Daguerre developed skills in panorama painting and architecture, which gave him a rather fabulous career in the theater. Daguerre's Diorama, a three-dimensional but miniature replica of a scene or series of scenes, became a popular mode of entertainment in Paris by 1822.

Daguerre's Diorama played with lighting effects to create illusions of moving images and reality. The diorama was the dawn of history of cinema and the moving image. Historic Camera writes, "Daguerre invented his incredible Diorama show becoming a pioneer in theater sets and what later evolved into the movie industry."

Partnership with Nicéphore Niépce: Pioneering the Camera

It's important to know that Daguerre's motivation behind the daguerreotype was the same for his diorama, which was to capture a scene of reality. So, despite the earlier invention's popularity and success, he remained curious and driven to create an improved invention. Meeting Nicéphore Niépce in 1828 prepared him for greater things.

According to the Britannica Encyclopedia, Niépce and Daguerre's partnership bloomed for a single, common goal—which was to be able to freeze a scene or image at one point of time and reality:

He opened the Diorama, an exhibition of pictorial views, with various effects induced by changes in the lighting. A similar establishment that he opened in Regent’s Park, London, was destroyed by fire in 1839. Niépce, who since 1814 had been attempting to obtain permanent pictures by the action of sunlight, learned in 1826 of Daguerre’s efforts in the same field.

With the partnership, Niépce was able to create heliography, a very early photographic process that used sunlight to draw the image. According to Photo Museum, Daguerre and Niépce also created the physautotype, another early photographic process which used silver plate and evaporated resin of lavender oil, then exposed to sunlight. Daguerre continued helping Niépce from 1829 until the latter's death in 1833. Daguerre continued to realize his goal and improve Niépce's discoveries.

The Daguerreotype: The First Commercially Successful Photographic Invention

One could say that Daguerre and Niépce differed on how they wanted the photographic invention to function. "Daguerre’s interest was in shortening the exposure time necessary to obtain an image of the real world, while Niépce remained interested in producing reproducible plates," says the Britannica Encyclopedia.

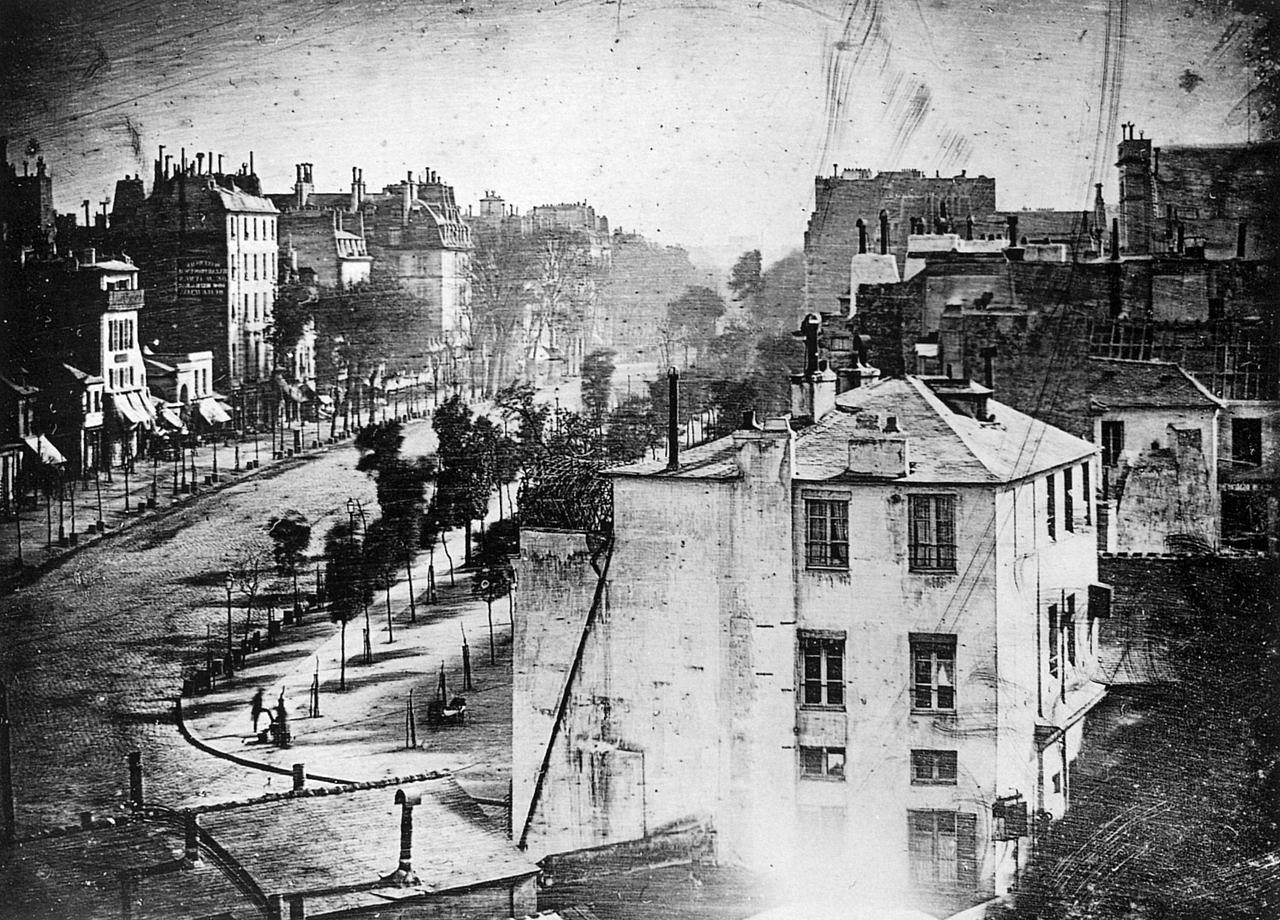

Three years after Niépce's death, Daguerre made a discovery that allowed him to reduce the exposure time from eight hours to 30 minutes. It was this feature that made the daguerreotype so popular. The Britannica writes further, "Daguerre had discovered that a latent image forms on a plate of iodized silver and that it can be 'developed' and made visible by exposure to mercury vapor, which settles on the exposed parts of the image."

Each daguerreotype was unique, often a portrait of famous and notable personalities. However, the invention was also used to shoot photos of items for scientific illustration. Compared to photographic paper, the daguerreotype is rather fragile and heavy, often encased in metal finishes for protection.

The history of photography had always been dual—for art and for science—and Daguerre took this advantage and promoted the daguerreotype to both sectors.

An International Legacy

History, in general, will forever remain incomplete, as many works and records will always be unheard and unseen. In 1988, Daguerre's laboratory and the majority of his works, records and early experiments caught fire. Fortunately, the few surviving relics of Daguerre were enough for history to immortalize his name and inventions. His process changed the history of art forever and pushed the history of photography to greater and bigger things.

It's important to note how desperate 20th-century artists and scientists were to have an invention that could capture reality at certain accuracy. The daguerreotype was the first photographic process that offered unmatched realism compared to painting and other reality-mimicking techniques.

The Franklin Institute wrote:

Daguerreotypes offered clarity and a sense of realism that no other painting had been able to capture before. By mid-1850's, millions of daguerreotypes had been made to document almost every aspect of life and death. Photography was on its way to becoming quite commonplace; portrait studios—and eventually, everyday picture-taking—would catch on in a flash.

While photography flourished further in Europe, American photographers started with the daguerreotype and stuck with this method for nearly 20 years. Samuel Morse, a man of science (also the inventor of the telegraph and the Morse code) and the first person to see and practice the daguerreotype, was fascinated by its accuracy. According to American Daguerreotypes, "[t]his discovery is, therefore, about to open a new field of research in the depths of microscopic Nature. We are soon to see if the minute has discoverable limits. The naturalist is to have a new kingdom to explore, as much beyond the microscope as the microscope is beyond the naked eye."

Across the Pacific, one of the pioneers of Japanese photography, Ichiki Shiro, created the first known Japanese photograph, a portrait of his daimyo Shimazu Nariakira with the daguerreotype.

The daguerreotype was nowhere near perfect, and its crucial flaw was its inability to capture fast-moving objects and people; but during its time, the daguerreotype seemed like a work of magic than of scientific invention. It showed how much photography progressed in a short period of time, and how much photography still has a long way to go. He left plenty of room for improvements.

While a new photographic invention after another continues to outdo each other, Daguerre's most essential gift to the world was that he laid the very foundation of the history of photography; a legacy unmatched.

Own your dreams and visions with Lomography's Daguerreotype Achromat Art Lens and bring the delicate aura of French Romanticism and Impressionism into 21st-century imagery!

2016-04-09

#gear #news #daguerreotype #achromat #artlens #lomographyartlenses #daguerreotype-achromat-art-lens

2 Comments